A Shepherd’s Glossary of Terms

Everyone is a beginner at some point in time…and the new words that come flying at us are confusing and at times overwhelming. I found that when I first learned to sail…why can’t they just call it the right side of the boat instead of starboard! Raising sheep can be easier if you know what everyone else, including your veterinarian, is talking about. I will start with the basics:

EWE – a mature female sheep

RAM – a male sheep that has not been castrated, also called a buck.

LAMB – a baby sheep; a sheep under a year old, i.e. a ewe lamb or ram lamb, a term for the meat of sheep, generally under 18 months old, preferably under 12 months old;

the term used for the birth of a baby sheep, i.e. The ewes are due to lamb in the spring.

YEARLING – a ewe or ram between 1 and 2 years old

WETHER – a castrated ram, also used to describe the act of castrating a ram.

SHEPHERD – one who tends to the every need of the sheep, loves them and worries over them and reaps the rewards of sheepkeeping!

BREEDING & LAMBING TERMS

BRED EWE – a ewe that is pregnant

A.I. – artificial insemination, a procedure done to a ewe by a trained person in which fresh or frozen sheep semen is introduced into the ewe to produce a pregnancy with that particular ram as the sire.

SIRE – father of a lamb

DAM – mother of a lamb

BREEDING GROUP – a group ewes placed with a particular ram for the purpose producing pregnancy in the ewes.

CLEAN-UP – the ram used for the next session of breeding after the original ram is removed from the breeding group to insure that all of the ewes are bred.

FLUSHING – The practice of increasing the body weight and condition of ewes prior to and after breeding to increase ovulation and conception.

HEAT – estrus, a term used to describe the period in the ewe’s life when she is able to be bred, which last about 30 hours. Ewes will have a heat or estrus cycle every 14-20 days, at the end of which they are ovulating and are receptive to being bred. Some sheep breeds cycle year round are able to be anytime during the year, while others, like Icelandic sheep, are very seasonal and only cycle in the fall and winter months. The first cycle generally occurs when the ewe is about 6 months old, though some may be younger.

GESTATION – the period between breeding and lambing, usually 142-147 days in Icelandic sheep, a few days longer in many other breeds.

S-T-Tr – Shorthand for Single, Twin, or Triplet, usually seen in listings of lambs for sale, telling the buyer if the lamb was one of one… or one of several.

UDDER – milk producing gland of the sheep, a bag like structure under the ewe between the rear legs that fills with milk at the end of pregnancy. The udder has two primary nipples or teats for the lambs to suck to get the milk.

LACTATION – the period of time when the ewe is producing milk.

JUG – a small pen used for just one ewe and her newborn lambs soon after they are born, used to keep an eye on the new family.

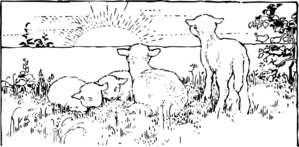

PASTURE LAMB – a system of lambing in which the ewes are left out in the pasture to have their lambs, rather than in a barn.

BUMMER/BOTTLE BABY – term used for a lamb that must be fed by the shepherd with a bottle and nipple because the dam is unable to feed the lamb, sometimes a bummer is a lamb that sneaks up behind an unrelated ewe and steals milk.

GENERAL ICELANDIC SHEEP TERMS

Probably the most confusing terms and concepts surrounding the Icelandic Sheep are the various colors and markings.

COLOR – refers to the color of the sheep, in Icelandic Sheep the color is always brown (moorit) or black. White is technically not a color, but a pattern: the pattern gene for “no pattern” turns off the color gene of brown or black to create “no color” or… white. That said, “color” can range from a deep black to a “rusty” black, Moorit (brown) can range from a light tan to a deep royal chocolate.

PATTERN – In Icelandic sheep, the pattern is one of 6 possibilities, white, grey, solid, badgerface, mouflon, or grey-mouflon. The Icelandic Sheep gets its fleece color from three genes: the basic color gene, the pattern gene, and the spotting gene. Making a total of 6 genes, inheriting 1 set of three from each parent. Color “coding” an Icelandic Sheep makes for some very complicated reading. The pattern “grey” for example is actually a colored overcoat (black or brown) with a white undercoat, creating “grey” which can be a black grey or “moorit,” meaning brown, grey. “Solid” is black on black or brown on brown, over and undercoat, creating a “solid” sheep. To achieve “solid” you need two copies of both the colored gene, and the “solid” pattern gene. The “Badgerface” pattern gene turns the back, sides, neck, face, and ears to a light tan or white… making the sheep’s face resemble a “badger.” The color of the sheep shows on the face and neck, the belly, and under the tail, creating either a “black” or “brown” badgerface. “Mouflon” is the opposite of badgerface.. so instead of the color being under the sheep, on the neck and belly, it is on the top of the sheep… creating a mirror image of the badgerface. We will also see a “Grey Badgerface” and a “Grey Mouflon” this is the two genes co-expressing in one sheep. There is a rare single gene, “Grey-mouflon” which is, as far as we know, not available in the United States. It is a unique gene which creates a sheep that looks like a combination of “grey” and “mouflon” having a more more pronounced marking pattern than either the grey or the mouflon, distinctly unique to itself.

The pattern “White” (absence of pattern) is dominant over “Grey,” “Badgerface” or “Mouflon”. “Solid” is recessive… it takes two solid parents to produce a solid black or moorit lamb. Remember “absence of pattern” means the white sheep IS still carrying two colored genes under the “wrapper” of the pattern “white.” So a white ewe bred to a solid moorit ram (who must carry the two recessive moorit color genes) who produces a black lamb, is carrying the color black. If she produces a moorit lamb, she carries moorit, if she produces a white lamb the best we can say is that her lamb carries moorit. We don’t know if she is carrying two dominant white pattern genes (and therefore overriding the recessive gene for “solid”) or if the throw of the dice just popped up the pattern “white” again. Remember, you can never breed two sheep who are not white, and produces a white. Never, ever. If you want white sheep, you need to have a white sheep!

SPOTTING – The third gene to influence the appearance of the sheep is the spotting gene. All Icelandics carry either spotting, or no spotting. If a sheep inherits spotting genes from sire and dam it will have random white spots within its overall pattern, since not spotted is dominant over spotted…

Confused? Join the club! ISBONA publishes a pdf file “coding the color/pattern genes for registration.” If you look it over you’ll be able to decipher the cryptic genetics of the registered Icelandic you’re looking at.

BROWSE – brush or woody plants that can be eaten, i.e. sapling trees, wild raspberries, wild roses etc.

CREEP – an area for feeding lambs with an entrance designed to allow lambs in but keep adult sheep out

CUD – a mouthful of regurgitated food rechewed and swallowed by the ruminant. The stuff that sheep are chewing while they are hanging out. Happy healthy sheep spend a good portion of the day and night chewing cud, breaking it down so that the bacteria in the rumen part of the stomach can get the nutrients out of the feed.

CULL – to remove an animal from the breeding flock because it does not meet the needs of that breeding program. It may fit well in another flock, unless cull for health reasons. Also, refers to an animal that has been culled.

DOCK – the procedure of cutting the long tails of newborn sheep to a short length. Unnecessary in naturally short-tailed sheep like Icelandics and Shetlands

FORAGE – the green edible part of the pasture eaten while grazing, the stuff hay is made of.

ROTATIONAL GRAZING – The practice of intensely grazing one area of pasture before moving the animals onto fresh graze, allowing the first pasture to recover before it is re-grazed. Increasingly popular, it allows for very efficient use of available pasture.

OPP – Ovine Progressive Pneumonia, is a slowly progressing viral disease, similar to the AIDS virus in humans. It is not transferable to humans. It slowly causes progressive lung damage, weakness, udder damage. There is no cure, but animals can be tested for the virus and culled. A negative OPP test, done by a reliable laboratory, means that on that date the animal was negative for OPP. OPP is a “purchased ” disease. Be sure to request that an animal is tested and quarantined before it enters your flock.

OVINE – referring to sheep

POLLED – naturally hornless. When shopping for lambs you may see a listing P-H-Sc. This stands for Polled, Horned, or Scurs, and describes what is on top of the lamb’s head!

PUREBRED – an animal with 100% of the bloodline is from the same breed.

REGISTERED – an animal that is purebred and meets the breeds standards and guidelines, and is officially recorded with an association or registry

RUMEN – the part of the sheep’s stomach where bacteria, yeast, fungi and protozoans breakdown the feed through fermentation. It has a 5-10 gallon capacity. Keeping the inhabitants of the rumen happy and healthy is a key part of the shepherd’s job

RUMINANT – animals that have a 4 compartment stomach such as sheep goats and cows, an animal that chews cud.

SCRAPIE – a TSE disease (transmissible spongiform encephalopathy),caused by a prion, similar to “mad cow disease” . Scrapie has been recognized for 200 years. So far it is not believed to be transferred to humans.

SCUR – a small horn, often misshapen, not firmly rooted in the skull

SPOTTING – a lack of pigment in the coat of the sheep that produces a “white spot” or absence of color.

VSFCP – Voluntary Scrapie Flock Certification Program, a voluntary program managed by the USDA (United States Department of Agriculture) for the surveillance of flocks to ensure the absence of Scrapie in the sheep. A federal veterinarian will annually inspect an enrolled flock. Each state has a VSFCP board and a procedure for enrollment. In order to AI breed or purchase AI bred Icelandic sheep, the flock must be enrolled. There is no fee for the enrollment or inspection other than the ID tags.

WOOL AND WOOL PRODUCTS

WOOL – A protein fiber produced by the follicles in the skin of the sheep.

DUAL-COAT – refers to the type of wool produced by Icelandic sheep and some other primitive breeds. Two distinct true wool fibers are produced simultaneously. In Icelandic sheep this is a long coarser outer coat called TOG, and a fine soft downy undercoat called THEL.

LANOLIN – the natural grease that occurs on wool

SECOND CUTS – undesirable short pieces of wool produced when shearing by going back over already sheared areas.

FLEECE – the wool sheared from one sheep

RAW WOOL – unwashed wool, also called wool “in the grease”

WOOL BREAK – In Icelandic sheep a naturally occurring actual break in the wool in the spring followed by a shedding process and regrowth of the new wool. “like spring break but different”

ROOING or ROOING OFF – when a sheep’s fleece starts coming off on its own. Usually in patches, usually your rams, and usually by rubbing it off on fences, trees, etc. A ram rooing off his fleece can end up dragging a great patch of felted wool until it finally tears free, or you cut it off.

SKIRT – to remove from the sheared fleece the parts that are unusable or undesirable for spinning, i.e. vegetation, manure, urine stained areas, felted areas

TAGS – wool locks that are contaminated with manure

ROVING – wool that is washed and carded into a form ready to be spun

CLOUD – a washed fluffy form of carded wool ready to be spun

LACEWEIGHT – a form of yarn that is used for knitting fine, ultra-light weight pieces. 1500-3000 yards/pound

SPORTWEIGHT – a form of yarn for knitting light to medium weight garments, ideal for hats, socks, mittens, and sweaters. 1000-1200 yards per pound

DK/WORSTED WEIGHT – a form of yarn for knitting medium to heavy weight garments, approximately 800-900 yards /pound

PLY – the number of strands combined to make one strand of yarn, i.e. single ply, 2 ply etc.

BATT – a carded form of wool, generally rectangular, used for spinning, felting or quilting

LOPI – a commercial brand of single ply Icelandic wool that has been commercially washed and dyed

SPRING CLIP – the winter wool sheared from the Icelandic sheep, often better suited to felting than spinning, usually shorter in length .

FALL CLIP – the premium fall fleece sheared from the Icelandic sheep, used for spinning and yarn

LAMB FLEECE – the first shearing of the lamb, usually in the fall. The premium spinning and yarn wool, the softest and often uniquely colored.

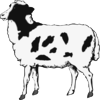

The horned rams will grow a fine set of curled horns similar to the wild Mountain Sheep in the Rockies. The ewes’ horns are C-shaped. The faces are open and the legs are also free of wool. The sheep are strong and healthy and prolific. They are long lived, the ewes bearing lambs into their 10th year and older. Having been raised in a grass based farming system in Iceland for the past 1200 years, they do not require expensive grain feeding to reach a respectable market weight. Most rams are sent to market at 5-6 months of age.

The horned rams will grow a fine set of curled horns similar to the wild Mountain Sheep in the Rockies. The ewes’ horns are C-shaped. The faces are open and the legs are also free of wool. The sheep are strong and healthy and prolific. They are long lived, the ewes bearing lambs into their 10th year and older. Having been raised in a grass based farming system in Iceland for the past 1200 years, they do not require expensive grain feeding to reach a respectable market weight. Most rams are sent to market at 5-6 months of age. The ewes are putting energy into their pregnancies and not into wool growth at that time. The ewes will shed the belly and udder wool and the wool around the crotch first so that shearing is not necessary prior to lambing. The wool can be plucked or “rooed” during the spring wool break but it is not a very efficient way to harvest the spring wool. Often the sheep sheds in patches and the fleece may be felted underneath as it loosens. Most Icelandic sheep here are sheared twice each year, once in the late winter or spring and again in the mid to late fall. The sheep grow wool amazingly fast. The shorter spring fleece is fine for felting and the longer clean fall fleeces are highly valued by handspinners.

The ewes are putting energy into their pregnancies and not into wool growth at that time. The ewes will shed the belly and udder wool and the wool around the crotch first so that shearing is not necessary prior to lambing. The wool can be plucked or “rooed” during the spring wool break but it is not a very efficient way to harvest the spring wool. Often the sheep sheds in patches and the fleece may be felted underneath as it loosens. Most Icelandic sheep here are sheared twice each year, once in the late winter or spring and again in the mid to late fall. The sheep grow wool amazingly fast. The shorter spring fleece is fine for felting and the longer clean fall fleeces are highly valued by handspinners.

Icelandic Sheep eat hay, and grass. The hay should be leafy green… alfalfa hay is wonderful, but not necessary. You should never feed moldy hay to sheep. You can feed in round bales if you have the equipment to handle the bales…but whatever you decide to do, you’ll need a reliable source of hay. Or two unreliable sources. You can have your hay tested for feed value if you like, 16% protein is pretty good grass hay. If your hay tests to around 8% you’ll want to supplement the hay with a little grain or alfalfa pellets, or even soy meal, which is a great source of protein.

Icelandic Sheep eat hay, and grass. The hay should be leafy green… alfalfa hay is wonderful, but not necessary. You should never feed moldy hay to sheep. You can feed in round bales if you have the equipment to handle the bales…but whatever you decide to do, you’ll need a reliable source of hay. Or two unreliable sources. You can have your hay tested for feed value if you like, 16% protein is pretty good grass hay. If your hay tests to around 8% you’ll want to supplement the hay with a little grain or alfalfa pellets, or even soy meal, which is a great source of protein. You’ll also need a supply of fresh clean water. Sheep need a regular source of clean water. Icelandic sheep want to drink a gallon of water a day when they’re pregnant, more when they’re nursing, and in the hot months of the summer, they’ll need to replace volumes of water. Please don’t underestimate the importance of having fresh water for your sheep… but you don’t want to rely on a farm pond unless you’re willing to watch the sides of the pond deteriorate. And the sheep will contaminate the pond. You’ll find a trough system, or even buckets filled regularly, preferable to the pond.

You’ll also need a supply of fresh clean water. Sheep need a regular source of clean water. Icelandic sheep want to drink a gallon of water a day when they’re pregnant, more when they’re nursing, and in the hot months of the summer, they’ll need to replace volumes of water. Please don’t underestimate the importance of having fresh water for your sheep… but you don’t want to rely on a farm pond unless you’re willing to watch the sides of the pond deteriorate. And the sheep will contaminate the pond. You’ll find a trough system, or even buckets filled regularly, preferable to the pond.

In addition we provide you with a year’s Newsletter Membership to Icelandic Sheep Breeder’s of North America

In addition we provide you with a year’s Newsletter Membership to Icelandic Sheep Breeder’s of North America

They know that they must have at least two sheep in the pen to keep each other company, so they decide they’d like to start with two ewe lambs: a white one and a black one. They contact us in January to reserve their ewe lambs so they won’t be disappointed in the spring, and at that time they also talk to us about getting a ram so they can have lambs of their own the following spring.

They know that they must have at least two sheep in the pen to keep each other company, so they decide they’d like to start with two ewe lambs: a white one and a black one. They contact us in January to reserve their ewe lambs so they won’t be disappointed in the spring, and at that time they also talk to us about getting a ram so they can have lambs of their own the following spring.

If it is cold I dry the lambs off with a towel after mom has had a chance to lick it…the licking stimulates lots of maternal responses and uterine contractions so she can deliver the twin if there is one. I wait for her to have a chance to nurse the lamb but sometimes they are obsessed with licking the lamb and keep turning around as the lamb just about gets to a teat…I give them 15 minutes, then take the lamb, milk a bit out of each teat to be sure the plug is removed and try to get it on a teat, even if I have to pin mom against a wall..not very graceful and usually they are fine, but a lamb with no milk is a dead lamb! Once they get a few good drinks it usually dawns on mom what this is all about. Some ewes are just great…they seem to have read the book..others need a little help to figure out the whole thing…first timers are just learning , just like first time human moms.

If it is cold I dry the lambs off with a towel after mom has had a chance to lick it…the licking stimulates lots of maternal responses and uterine contractions so she can deliver the twin if there is one. I wait for her to have a chance to nurse the lamb but sometimes they are obsessed with licking the lamb and keep turning around as the lamb just about gets to a teat…I give them 15 minutes, then take the lamb, milk a bit out of each teat to be sure the plug is removed and try to get it on a teat, even if I have to pin mom against a wall..not very graceful and usually they are fine, but a lamb with no milk is a dead lamb! Once they get a few good drinks it usually dawns on mom what this is all about. Some ewes are just great…they seem to have read the book..others need a little help to figure out the whole thing…first timers are just learning , just like first time human moms.

If you know that you may have a problem situation and may need to graft a lamb, try to save the placenta or birth fluids from the ewe that is to receive the new lamb. If her lamb is stillborn, save the dead lamb and placenta in a bucket. If you are going to give a ewe an extra lamb, try to save her placenta and any birth fluid or tissues from her own live lamb in a plastic bag.

If you know that you may have a problem situation and may need to graft a lamb, try to save the placenta or birth fluids from the ewe that is to receive the new lamb. If her lamb is stillborn, save the dead lamb and placenta in a bucket. If you are going to give a ewe an extra lamb, try to save her placenta and any birth fluid or tissues from her own live lamb in a plastic bag. If the lamb to be grafted is from a dead mother, the situation is a little different. If there isn’t a ewe lambing, you will have to give that newborn a bottle of colostrum milked from another ewe ( or from your frozen stash) until there is an appropriate recipient mom. I find it helpful to wash the lamb in clean warm water too. If you had a ewe that had a single and could easily handle twins and your were fortunate to have saved her placenta, the procedure is nearly the same. You will wash the lamb, and then put it in a basin of a little warm water and stick the ewe’s own lamb in there too. Give the Oxytocin and do the internal stimulation if the ewe is within 24 hours or less from having given birth. You will use the soft twine to tie the legs of the lamb to be grafted. Tie the front legs together, and the back legs together. The ewe is less suspicious if the “graftee“ isn’t running around. It will struggle to get up , much like a newborn. Put it in with the ewe and her other lamb in a jug, so the original lamb can’t be running off, taking mom with it. If mom is ignoring the new lamb , tie the legs of the other lamb and put the two together in front of the ewe. Get the new lamb to nurse as soon as you can. You may have to take the original lamb away to let mom bond with the new one. You can put more of the “placenta water” on the two lambs if needed., especially on the butt end of the lambs, and the top of the head.

If the lamb to be grafted is from a dead mother, the situation is a little different. If there isn’t a ewe lambing, you will have to give that newborn a bottle of colostrum milked from another ewe ( or from your frozen stash) until there is an appropriate recipient mom. I find it helpful to wash the lamb in clean warm water too. If you had a ewe that had a single and could easily handle twins and your were fortunate to have saved her placenta, the procedure is nearly the same. You will wash the lamb, and then put it in a basin of a little warm water and stick the ewe’s own lamb in there too. Give the Oxytocin and do the internal stimulation if the ewe is within 24 hours or less from having given birth. You will use the soft twine to tie the legs of the lamb to be grafted. Tie the front legs together, and the back legs together. The ewe is less suspicious if the “graftee“ isn’t running around. It will struggle to get up , much like a newborn. Put it in with the ewe and her other lamb in a jug, so the original lamb can’t be running off, taking mom with it. If mom is ignoring the new lamb , tie the legs of the other lamb and put the two together in front of the ewe. Get the new lamb to nurse as soon as you can. You may have to take the original lamb away to let mom bond with the new one. You can put more of the “placenta water” on the two lambs if needed., especially on the butt end of the lambs, and the top of the head.